It was a romance that helped inspire one of the great works of 20th-century fiction and a bitter conflict between his heirs, but a new book of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry ’s love letters to be published on Thursday suggests a reconciliation may finally have been achieved.

The Little Prince, by the French aviator, poet and war hero Antoine de Saint-Exupéry is said to have sold more than 200m copies in 450 different translations since it was first published in 1943.

Much of the story hinges around the mysterious star-travelling prince’s relationship with a rose – delicate and demanding – that he has been tending on his home planet.

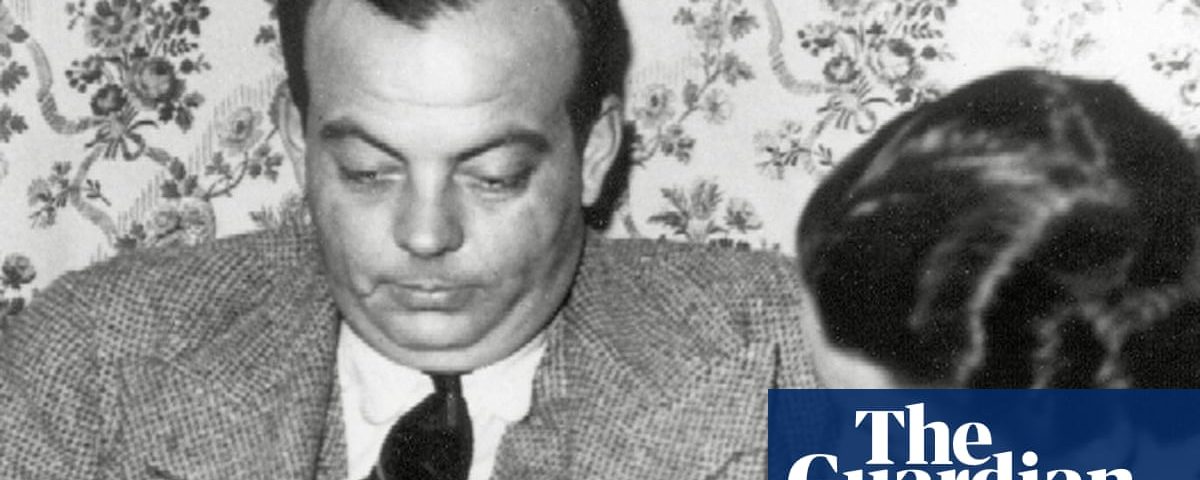

Saint-Exupery’s real-life rose was Consuelo Suncin, a Salvadoran artist who cut a swathe through high society in Latin America and beyond before marrying him in 1930.

Now, more than 160 of their letters and telegrams are being published in France , adorned with dozens of their sketches, photographs and other mementoes.

Unsurprisingly for a marriage between a moody, philandering adventurer and an intensely spirited and sharp-tongued artist, it was tempestuous.

“Consuelo my dear, you do not understand how much you make me suffer,” he writes at one point.

“I cry with emotion, I am so afraid of being exiled from your heart,” she responds.

There were many break-ups and affairs, though just as many reconciliations.

Biographer Alain Vircondelet told AFP: “Consuelo had an exuberant temperament, and he was a great depressive. His multiple affairs were not the sign of a Don Juan, but of an emotional failing.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince illustration up for auction Read more But there seems little room for doubt about their underlying feelings in one of Saint-Exupery’s final letters, when he writes: “Consuelo, thank you from the bottom of my heart for being my wife … If I am killed, I have someone to wait for in eternity.”

Saint-Exupery, who had joined the French resistance forces from exile in the United States, disappeared shortly after setting off on a reconnaissance flight from Corsica in July 1944.

No evidence of the crash was discovered until 1998 when a Marseille fisher pulled up a silver identity bracelet . It bore both their names.

Saint-Exupery’s aristocratic family were never keen on Consuelo and after his death all but airbrushed her out of his life story.

“Marrying a foreigner was considered worse than marrying a Jew,” one member of the family told biographer Paul Webster in the 1990s – giving a clear sense of the family’s politics.

She took her revenge, in Webster’s words, by handing her half of the royalty-rights to her gardener-chauffeur José Fructuoso Martinez when she died in 1979, along with a huge haul of the love letters.

In 2008 the Saint-Exupery family successfully sued him after he published a book about Antoine and Consuelo’s relationship without their permission.

Six years later however he successfully sued them to make them pay him a share of revenues from a cartoon version of the book.

The publication of the love letters represents a reconciliation between the rival estates.

In a press release last month via French publisher Gallimard, the author’s descendants spoke of a “fruitless 18-year legal war” before they agreed to collaborate on the project.

French scholar Alain Vircondelet, an expert on the writer, says much more correspondence remains unseen. It is now held by the gardener’s widow, Martine Martinez Fructuoso.

“She possesses a colossal treasure on Saint-Expury, and every time she tells me about it, I am astonished,” Vircondelet told AFP.

Still, at the heart of the story is a romance that sparked one of literature’s most enduring and popular tales, and its roots can be seen in the very first letter Saint-Exupery wrote to his future wife.

“I remember a very old story, I’m changing it a little,” he writes, shortly after they met in Buenos Aires.

“There was a small boy who discovered a treasure. But the treasure was too beautiful for a child whose eyes didn’t know how to comprehend it or his arms to hold it. So the child grew sad.”